Sarabande

0:00 Opening music: The G major sarabande, BWV 1007, with the dancing feet of Paige Whitley-Bauguess. All manuscript examples of Bach’s sarabandes for cello, unless otherwise indicated, are from the source in Anna Magdalena’s hand.

0:07 Bach wrote more sarabandes than any other dance type if you include all of the doubles (variation movements). The orchestral suite No. 2 in B minor, BWV 1067, is the notable exception among the predominantly solo sarabandes. Chapter on Sarabande, Little/Jenne, Dance and the Music of J.S. Bach. See also the work’s Appendix B for a list of sarabande-like rhythms in Bach’s larger instrumental and vocal works.

“I Can’t Dance to That!“

1:24 Photo Sequence:

- Paige Whitley-Baugess in Spanish attire with castanets

- in Armide

- in rehearsal (photo by Barry Bauguess)

The Slow Movement of the Suite?

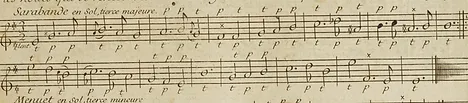

3:40 Sequence of musical images:

- Lully, Le Bourgeois Genthilhomme, Act Premiere, premiere Intermede, p. 31

- Georg Muffat, Florilegium Primum, Suite 1, Eusebia.

- Leclair, Première récréation de musique, Op.6

- Tomlinson, Kellom. The art of dancing explained by reading and figures, p. 100.

- Tomlinson, Kellom. The art of dancing explained by reading and figures, p. 98.

4:19 Metronome marks are ball-park estimates given by Paige Whitley-Bauguess. The choreography for Tomlinson’s “very slow” sarabande is quite spare. There are few movements per beat and so maintaining balance is quite difficult in a tempo slower than about 69 or 72 to the quarter note.

4:51 Lully, Le Bourgeouis Genthilhomme, Act V, Troisieme Entree, p. 159. Spanish and Italian sarabandes, often featuring quarter note rhythms, tended towards faster tempi. This choreography to the Air des Espagnols appears in Feuillet’s Choregraphie for a female dancer on pp. 21-24, and for a male dancer on pp. 25-28.

5:12 Danced segment from Sarabande No. 1 in G major. Video of a rehearsal for a performance for the Atlantic Baroque Dance Theatre. Edited by Paige Whitley-Baugess.

Fit For a King

5:53 Engraving of a 1682 ball given by Louis XIV of France (Almanac royal). Loius XIV and Madame de Pompadour. The music at the bottom of the engraving is a minuet by Charpentier.

6:03 François-Antoine Pomey, Description d’une Sarabande Dansée, 1671. Translated by Patricia Ranum, Audible Rhetoric and Mute Rhetoric.

This fascinating description appears at the end of the dictionary (more than 1000 pages long) among other such depictions: A description of the fireworks made for the festival of Versailles; A duel on horseback; A bold and valiant man in a fight; The countenance of a man in anger; A warrior, modest after victory; The portrait of an accomplished princess, and more.

A Beautifully Balanced Form

7:22 There are 27 known sarabande choreographies. The extant notations are meticulously catalogued in two publications: Little/Marsh, La Danse Noble; Lancelot, La Belle Dance.

7:25 Dance manuscript sequence:

- Sarabande de M. Fueillet, Polixene et Pihrrus, III, 8 (1706) by Paul Colasse

- Discussion of source by Paige Whitley-Bauguess

- La Royalle. Pécour, Guillaume-Louis. Nouveau recüeil de dance, c. 1713, p. 1

- Sarabande de M. Beauchamp

- provided by University of Salzburg, Derra de Moroda Dance Archives, DdM 797

7:50 Of the 31 titled sarabandes by Bach, only two contain sections not divisible by 4. The B sections of the keyboard partitata BWV 828 and BWV 1013 for solo flute contain respectively 26 and 30 bars.

7:53 Tomlinson, Kellom. The art of dancing explained by reading and figures, p. 98.

The symbol (=) in bar 4 indicates a “bound,” which Tomlinson describes as a kind of spring from one foot to another, p. 34.

8:20 G Major sarabande with larger rhythmic structure.

A Very Special Second Beat

9:56 D minor Sarabande opening bars

10:20 C major Sarabande opening bars

10:43 G major Sarabande opening bars

10:52 G major Sarabnade, bars 13-14

Ups and Downs

11:32 The line, “It’s not the bowings that make the music, but the music that makes the bowings,” I blatantly stole from my colleague in The Vivaldi Project, Elizabeth Field, who is a great source for such clever lines.

11:52 Rhythmic patterns are adapted from Fig. VII-3 in Little/Jenne, Dance and the Music of J.S. Bach, p. 92-103. The bowings are my addition, based on the writings of Georg Muffat, the self-appointed ambassador of French style to German Lands, and particularly the Lullian style.

Note: These bowings are assuming an overhand hold, used in a way that conforms to modern understanding of the association between down bows and strong beats and up bows and weak beats. Discussion of the underhand hold and possible variations in use of the overhand hold will be discussed in the project introduction.

Among Muffat’s bowing examples, none are specifically labelled sarabande, but he does offer a triple meter example of a quarter note rhythm in a slow tempo.

“Of the three notes which make up a whole measure in triple time, the first would be played down-bow, the second up-bow, and the third down-bow, when played slowly . . . this means one would play two down-bows in a row at the beginning of the following measure.”

Muffat also explains that in the case of dotted notes, it is permitted to take the shorter note in the same bow as the previous note as the need arises.

Florilegium Secundum, 1698. Translated by David K. Wilson in Georg Muffat on Performance Practice.

12:05 Early 18th-century French string methods were also consulted.

Corette, Michel, Méthode pour apprendre le violoncelle (1741). p. 26

Dupont, Pierre. Principes de violon par demandes et par réponce (1740), p. 6

Montéclair, Michel de. Méthode facile pour apprendre à jouer du violon (1711-12), p. 15

Michel de Monteclair’s reputation as a musician lay primarily in his teaching (he taught the children of François Couperin) and as an innovative orchestrator. In his violin method (1711-12), he provides two sets of bowings, one above the notes and one below. He explains that some do one, and some the other, but the bowings placed below the notes are generally adopted by “skilled players.” As we see in the sarabande example below, the lower set generally follow the established Lullian pattern, while in the set above, the notes allow for a more “as it comes” bowing. This occasionally results in up bows on down beats, although never for the beginnings of the four bar phrases.

Pierre Dupont was a violin teacher and dancing master. His treatise on violin playing was first published in 1718, and reprinted in 1740. Written in the format of a pupil asking questions of the teacher, Dupont explains that the reason he does not continue to indicate t (down bow) and p (up bow) for the second and third phrases, is that the bowing remains the same. Reflecting strict Lullian bowing practices, he explains that when the bow does not fall according to the rule, such that the first beat of the bar would arrive as a down bow, one simply retakes the bow as in the first phrase.

Michel Corrette was a prolific composer and wrote nearly 20 method books for various instrumunts, notably L′école d′Orphée, a violin treatise describing the French and Italian styles. Though he does include examples of sarabandes in both his violin and cello methods, they do not include bowing indications. The example used in the video is likely not a sarabande.

It should also be noted that there were two distinct manners of holding the bow: the ‘French’ grip where the thumb was held under the hair, and the ‘Italian” grip, much like what we use today, with the thumb between the hair and the stick. Both styles existed in the 16th and 17th centuries and even into the 18th. The ‘French’ grip was probably no longer used by the end of the 17th century in Italy, but remained popular in France until around 1725 when the style of Italian sonata playing became so influenital. See Wilson, Georg Muffat on Performance Practice, p. 109; Boyden, The History of Violin Playing, p. 152.

Montéclair describes the French style for holding the bow, while Dupont does not mention how it should be held. The French style works very well for the rhythmic and articulate strokes of dance music, while it is easy to see why the Italian style, offering greater flexibility and nuance, ultimately predominated. It is worth experimenting with both grips to experience the advantages of each for oneself.

12:33 Georg Muffat, Florilegium Secundum, 1698. Translated by David Wilson.

13:35 Opening of the D major Sarabande on a 5 string cello.